by Dr William C. Meyers

There is no more important area of the body for an athlete than the core, the region of our body from our chest to our knees. The core is our engine, our hub of activity. Strength there makes life easier for shoulders and knees. It produces speed and explosiveness. Endurance and grit.

Many rehabilitation specialists understand the core is vital for performance. But why has it remained such a medical mystery? No area of the body is more misunderstood than the core. For many professionals across the universe of sports medicine, truly understanding the core involves breaking down its common myths in order to see it with new eyes.

Myth #1: The Core Is Essentially a Strong Set of Abs and Lats, Right?

As therapists, you are intimately involved with power of the core. And maybe some of you understand that the core is much more than the beach muscles found in an abdominal 6-pack. You can’t blame regular folks for thinking the core is limited to the stomach area. That’s what they hear whenever core strength and fitness are discussed. Strengthen the middle and everything is fine. There’s nothing said about the other stuff—chest, upper thighs, rear end—and certainly nobody is talking about the genitals or pubic bone.

Ever since athletes, members of the military, or gym class students were forced to do calisthenics, there has been an interest in building a strong stomach. And as the fitness craze has boomed, trainers and other workout warriors have concocted new regimens to widen the area of attention. People are getting more powerful throughout their cores, and performance on all levels is improving. However, the medical community has been reluctant to define and address the core. Because it incorporates so many different surgical disciplines—general, orthopedic, thoracic, neurologic, etc—no one person can handle all of it. It’s unreasonable to think someone who specializes in pulmonary concerns would know the first thing about handling muscle tears in the groin area. As a result, the specialists have stuck to their areas, and instead of being considered as one entity, the core has been attacked in a piecemeal matter.

In the past, we have thought about all the different physiologic systems in this part of the body as separate species. It turns out that these species work together effectively as one cooperative species.

Myth #2: The Sports Hernia

One big thing I hope to eradicate is the term “sports hernia” forever from the English language. Or die trying. There is no such thing. Core injuries involve tears, pulls, and strains. They involve disruptions of big bony, muscly joints. They aren’t simple protrusions or bulges. And they aren’t simply hernias to be repaired by mesh.

The media gets part of the blame for this. Using the “sports hernia” catch-all term is easy and doesn’t require detailed explanations. We, the medical and health care communities, deserve some responsibility here, too. A huge number of publications perpetuate that term or terms that imply that repairs of hernias will fix that one type of problem. The anatomic region seems so complex. This complexity makes physicians give up trying to understand the problems more, and therefore lends itself to easy-to-say, catch-all phrases—even though we all know the terms have no validity.

There’s an awful lot going on in the core, what with all the biomechanics and the big blood vessels and organs in there. Orthopedic surgeons tend to stay away from that stuff. Neurosurgeons will take on the spine but aren’t about to go near the pubic bone. Other specialists—GI surgeons, urologists, and gynecologists, to name a few— see the core’s muscles and bones simply as the black box that encloses their provinces. For too many years, we have ignored the core, and that means we haven’t known what’s going on.

Myth #3: Rest Is Always Best

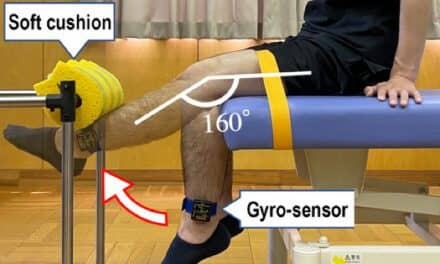

While certain core muscle injuries can heal with rest and activity modification, proximal avulsions and other muscular strains do not. It is important to determine the nature of the core muscle injury before prescribing rest. We see many athletes who are recommended rest for 6 weeks or more, in hopes a proximal injury will heal. This extended rest oftentimes causes athletes to miss complete seasons and pivotal events in their career.

Similar to an ACL rupture, it is possible to strengthen the surrounding musculature but there is still an underlying instability which prevents performance at a high level. When a surgical core muscle injury is identified and fixed, athletes are often able to return to full play in 6 weeks and then have the benefit of knowing the pathology has been repaired.

Myth #4: Core Injuries Are Isolated

Athletic trainers are educated and trained to determine if an injury is muscular, bone or nerve related, etc. They perform manual tests to assess the injury and understand that there may be referred pain coming from another location.

However, core injuries may not be as “straightforward” as, for example, an ACL tear where the location of pain is directly where the injury is. Understanding that groin pain may not be only caused directly by a muscle injury is important. It is not uncommon for the hip joint to be a culprit. Yes, the pain main be partly caused by a local strain or tear of one or more of the muscles of the groin, but there may also be compensation and tightening of the muscles due to an underlying hip pathology, like a labral tear or FAI.

The hip and pelvis are intimately involved and can work to “protect” each other when one or both have an injury. An athlete’s pain can be a combination of issues that should be addressed.

Myth #5: Core Muscle Injuries Mean a Missed Season

It turns out that early activation of the core muscles following repair is essential. Immediately following repair the two processes that are most likely to cause problems with return to play (scarring and loss of muscle tone) have already kicked in. Understandably, folks are nervous about re-injury and intuitively want to off-load and rest the repaired muscles.

But this is simply wrong. The body rapidly applies inelastic scar tissue to the area and, unopposed, results in constriction of the muscle compartment (akin to a compartment syndrome in the lower leg) and decreased flexibility to passive stretch. Couple the scarring with the loss of strength that comes with disuse, and you will have frustration and pain when you finally try to get back to training.

There may be a very real fear of early return to skill sets. It turns out that gentle soft toss catch for a baseball player or quarterback or careful, controlled skating for an NHL hockey player is good when instituted very early in the rehab program. It helps both with respect to preventing scar in key areas as well as allowing the player not to avoid the feeling of having to start from “scratch” when resumption of play really begins.

Rehabilitating any core injury requires a detailed understanding of the core anatomy, a good foundation of training, a willingness to be aggressive and adapt to changes as they arise, and persistence to push through setbacks and find the right help when things aren’t working. Specifically, the postop protocol we follow emphasizes immediate activity, with physical therapy beginning the day after surgery and walking a mile the day after surgery. Then we work on static strength and progressing to functional activities over the course of a 4- to 6-week time frame, aiming to have a full return to play at 6 weeks postop.

As Marshawn Lynch said recently, “To understand the core, you must put on new eyes.” By demystifying the core – the body’s power plant – we are allowing athletes of all abilities to improve their performance by strengthening and building the core to peak levels. This broader awareness and new approaches to core injury prevention, injury diagnoses, correction, and rehabilitation are shaping a new paradigm of the critical importance of core health.

William C. Meyers, MD, has dedicated 30 years to pioneering the diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention of core muscle injuries. He is the author of the recently published Introducing the Core: Demystifying the Body of an Athlete. Dr Meyers led the awareness that the whole core complex, inclusive with the hip joint, contributes to the injuries and has advanced new terminology that has replaced “sports hernia,” etc. He has evaluated over 25,000 patients, including many professional players from the NFL, NHL, NBA, MLB Premiership and other soccer leagues, tennis, golf, bull-riding, and track and field. He also treats many “weekend warriors” and non-athletes with pain in the core.

In 2013, Dr Meyers established the Vincera Institute, a center dedicated to the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, research, and education of core injuries. The institute includes participation from all the Philadelphia medical schools, plus the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City and Duke University Health System in Durham, NC.

Dr Meyers received his BA from Harvard University, MD from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, and MBA from the Wharton School. He completed his residency and fellowships at Duke University, where he remained on the faculty as Professor and Chief of General Surgery and other divisions of surgery. There, he developed the largest liver surgery service in the country.

He came to Philadelphia in 2001, where in deanship and other roles, he helped lead and preserve the medical school that survived the Allegheny bankruptcy, and guide it into the creation of Drexel University College of Medicine. Meyers was previously continually funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and V.A. Merit Review System, and has received various industry grants for research. He has authored or co-authored over 300 peer reviewed medical publications and the first modern textbook on liver and biliary surgery.