In a recent news release, researchers at the NYU Langone Medical Center report that air pollution has been linked to a dangerous narrowing of neck arteries that occurs prior to strokes. The release issued by the organization notes that the results yield from the analysis of medical test records for more than 300,000 individuals living in New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut.

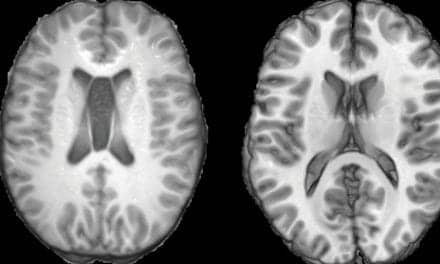

Scientists state that individuals living in ZIP codes with the highest average levels of fine-particulate-matter pollution were significantly more likely to show signs of stenosis in their internal carotid arteries, compared to those who were living in ZIP codes with the lowest pollution levels.

The release states that the study is slated to be presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 64th Annual Scientific Session and published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

Fine particulate matter pollutants, also known as “PM 2.5 pollutants,” are particulates with diameters less than 2.5 millionths of a meter. The release adds that they are primarily by-products of combustion engines and burning wood.

Much thought is put into the conventional risk factors for stroke, such as high blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking, says Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, senior investigator, assistant professor in NYU Langone Medical Center in the department of Medicine, Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology.

Yet, Berger adds in the release, “our data underscore the possibility that everyday air pollution may also pose a significant stroke risk.”

According to the release, medical researchers have observed since the 1950s that episodes of high air pollution can bring temporary jumps in local stroke and heart attack cases. Additionally, recent studies have reportedly linked stroke and heart attack risks to long-term pollution exposures as well, including PM 2.5 exposures.

In the release, Jonathan D. Newman, MD, MPH, study lead author and a cardiologist at NYU Langone Medical Center in the department of Medicine, Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology, explains that many studies “in this area have focused on the heart and the coronary arteries; no one has really looked at other parts of the vascular system, in particular the carotid arteries.”

During the study, the release says the carotid narrowing data came from vascular ultrasound tests performed on 307,444 tri-state area residents during 2003 to 2008 by Life Line Screening, a community-based health screen company focused on evaluating risk factors for vascular disease. Individuals with known carotid artery disease at the time of their ultrasound test were excluded from the dataset. The pollution data for the period came from the Environmental Protection Agency, the release says.

The analysis indicated that subjects in the top fourth of tri-state ZIP codes, ranked by average PM 2.5 levels, were about 24% more likely than those in the bottom quarter to have shown signs of stenosis—defined as a narrowing by at least half—in either internal carotid artery.

Newman acknowledges that “Our study was a population study, so it can’t establish cause and effect, but it certainly suggests the hypothesis that lowering pollution levels would reduce the incidence of carotid artery stenosis and stroke.”

The release adds that scientists are not yet certain how air pollution contributes to vascular disease. Past research suggests air pollution may do this by causing adverse chemical changes to cholesterol in the blood, by promoting inflammation, and by making blood platelets more likely to form clots.

The release notes that the study was a collaborative effort between researchers and clinicians in Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology and the Departments of Environmental Medicine and Population Health at NYU Langone Medical Center.

Additionally, the team plans to engage in further studies.

Berger points out that questions still linger: “Does the relationship between pollution levels and carotid artery stenosis hold up on a national level? Are certain groups disproportionately affected by air pollution? Is pollution also linked to other types of vascular disease, such as in your leg? There are a lot of questions we have yet to answer.”

[Source: NYU Langone Medical Center]