Macrophage cells are critical to growing muscle tissues in a lab, suggest biomedical engineers from Duke University. This discovery may play a role in studying degenerative muscle diseases and enhancing the survival of engineered tissue grafts in future cell therapy applications.

Results from the study are published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

In 2014, researchers led by Nenad Bursac, professor of biomedical engineering at Duke, debuted self-healing, lab-grown skeletal muscle. This was obtained by taking samples of muscle from rats just 2 days old, removing the cells, and “planting” them into a lab-made environment tailored to help them grow.

For potential applications with human cells, however, muscle samples would be mostly taken from adult donors rather than newborns. Many degenerative muscle diseases do not appear until adulthood, and growing the muscle in the lab to test drug responses for these patients would benefit from the use of the patient’s own adult cells.

There’s just one problem — lab-made adult muscle tissues do not have the same regenerative potential as newborn tissue, explains a media release from Duke University.

“I spent a year exploring methods to engineer muscle tissues from adult rat samples that would self-heal after injury,” says Mark Juhas, a former Duke doctoral student in Bursac’s lab who led both the original and new research.

“Adding various drugs and growth factors known to help muscle repair had little effect, so I started to consider adding a supporting cell population that could react to injury and stimulate muscle regeneration,” Juhas adds. “That’s how I came up with macrophages, immune cells required for muscle’s ability to self-repair in our bodies.”

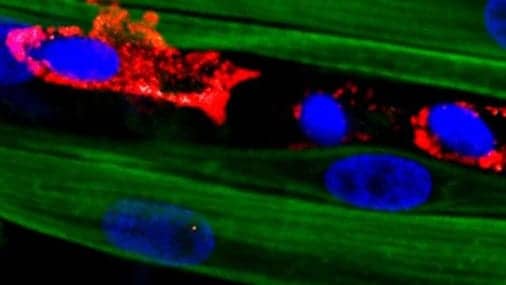

After a muscle injury, one class of macrophages shows up on the scene to clear the wreckage left behind, increase inflammation and stimulate other parts of the immune system. One of the cells they recruit is a second kind of macrophage, dubbed M2, that decreases inflammation and encourages tissue repair. While these anti-inflammatory macrophages had been used in muscle-healing therapies before, they had never been integrated into a platform aimed at growing complex muscle tissues outside of the body, the release continues.

“When we damaged the adult-derived engineered muscle with a toxin, we saw no functional recovery and muscle fibers would not build back,” said Bursac, who is a co-director of Duke’s Regeneration Next initiative. “But after we added the macrophages in the muscle, we had a wow moment. The muscle grew back over 15 days and contracted almost like it did before injury. It was really remarkable.”

Bursac believes the discovery may lead to a new line of research for potential regenerative therapies.

“We believe that the macrophages in our engineered muscle system may behave more like the muscle-resident macrophages people are born with,” Bursac continues. “We are currently working to understand if this is indeed the case. One could then envision ‘training’ macrophages to be better healers in a system like ours or augmenting them by genetic modifications and then implanting them into damaged sites in patients.”

[Source(s): Duke University, Science Daily]